18 months after I last took a train, I am back at the station. Nervous and flitting about, I constantly adjust my mask, side-eyeing anyone who isn’t wearing one or has it on wrong. I’ve never been as exhausted prior to starting a journey.

But stations are large areas, and I find myself a quiet spot waiting for my train to Arsikere to arrive. Arsikere is a small town about 3 hours north-west of Bangalore. No one really visits the place; but for those who like quiet railway junctions with giant trees that provide day long shade while reading, there really is no other place like it.

Not much afterwards, my train arrives and I am surprised to find that I am the sole occupant of my coach. The mask is triumphantly removed.

We leave Bangalore rapidly and are soon clattering through the countryside, stopping at small stations with huge trees on the platforms.

After a while, I busy myself alternately reading and looking out of the window

when a slight tang of the kere (lake) tells me that Arsikere is approaching.

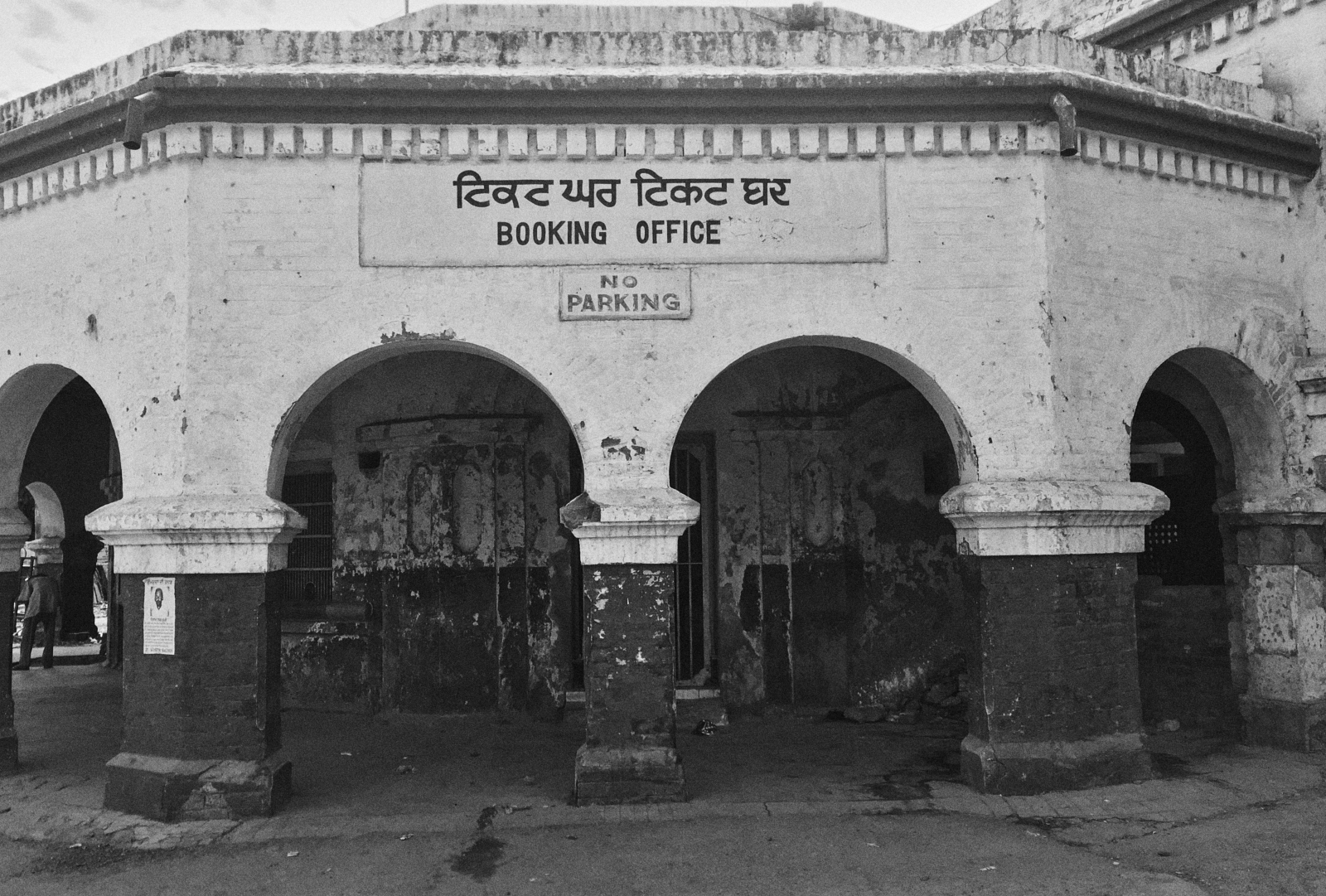

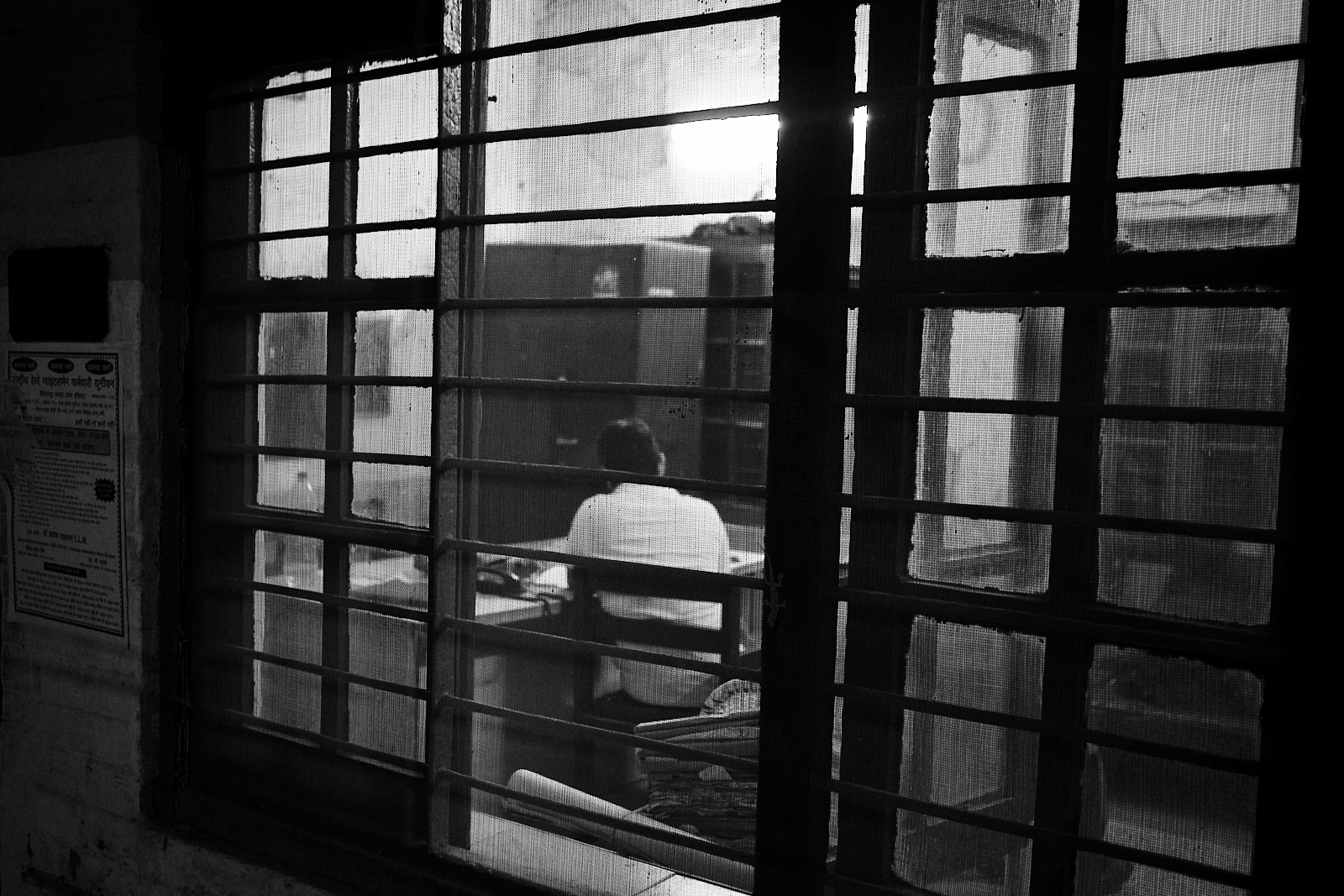

Five minutes later, I say goodbye to my coach and start walking around the station. And it an absolute delight.

It is by now lunch time and I head outside to the adjacent staff colony which houses one of the best canteens in all of the Indian Railways. Simple, cheap food that’s always served hot.

Post the superb lunch, I decide to take advantage of the cool weather and wander around the quaint staff colony, where the flowers are in full bloom!

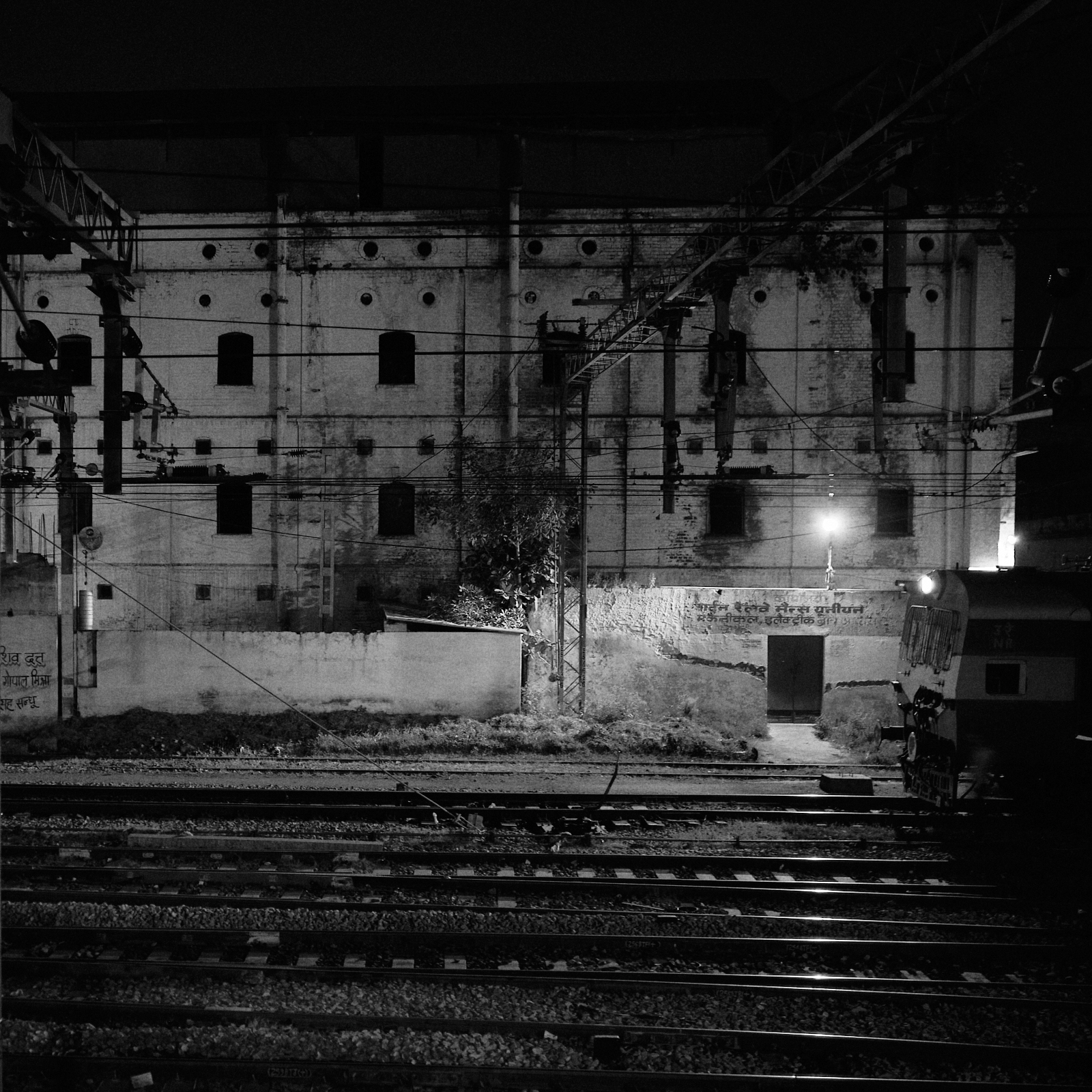

The entire junction is visible from the footbridge that spans the tracks and connects the two halves of the colony. On the platform is a train bound for Kochuveli (in Kerala).

I hang out on the bridge for a good half hour, before heading back to the station and catching up on the reading. The return to Bangalore is uneventful, but a lot more crowded. I am anxious throughout, but also delighted that I stepped out into the world for a day and felt normal.